A Policy That Misses the Mark

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, long a lifeline for millions, now faces a troubling shift. A recent USDA memorandum, issued on April 17, 2025, doubles down on enforcing work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents, known as ABAWDs. The directive, championed by Secretary Rollins, insists states tie SNAP benefits to employment, framing it as a path to self-sufficiency. But this approach, cloaked in the rhetoric of empowerment, ignores a harsh reality: these rules often leave the most vulnerable without food or opportunity.

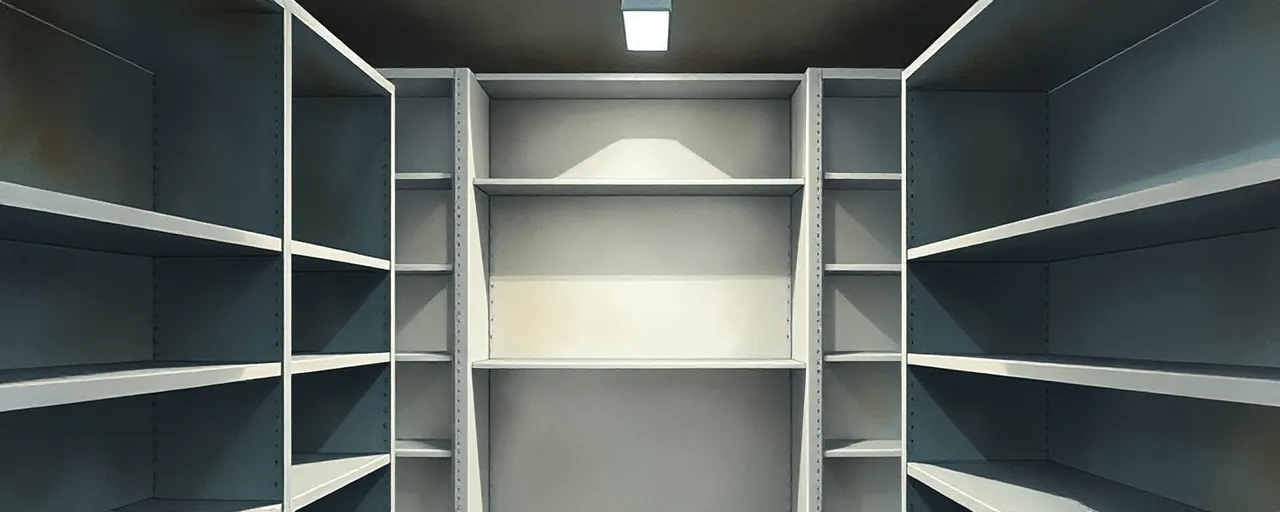

For those scraping by, SNAP offers a fragile buffer against hunger. Yet, the push to prioritize work over assistance assumes jobs are plentiful and accessible, a notion disconnected from the lives of many recipients. In a nation where economic distress lingers, particularly in underserved communities, the USDA’s stance feels less like a hand up and more like a door slammed shut. The memorandum’s emphasis on curbing waivers, which allow states to exempt recipients in high-unemployment areas, signals a troubling pivot toward punishment over pragmatism.

This isn’t about encouraging work; it’s about shrinking a program that serves one in seven Americans. The USDA’s renewed focus on enforcing time limits, where ABAWDs lose benefits after three months unless they work 80 hours monthly, risks deepening food insecurity. Research paints a stark picture: work requirements slash SNAP participation by 23-25%, yet yield no meaningful uptick in employment. For those already grappling with unstable housing or chronic health issues, this policy isn’t a nudge toward self-reliance. It’s a shove toward despair.

The Myth of Work as a Cure-All

The USDA leans heavily on the 1996 welfare reform, specifically the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, to justify its stance. That law, signed by President Clinton, introduced work requirements to reduce dependency. But nearly three decades later, evidence undermines its promise. Studies, including recent analyses of administrative data, show that work requirements for ABAWDs lead to plummeting SNAP enrollment without boosting earnings or job stability. The main outcome? People lose benefits, not poverty.

Consider the lived reality. Many ABAWDs face barriers that make steady work elusive: irregular schedules, caregiving duties, or simply no jobs in their area. The USDA’s memorandum nods to waivers for regions with unemployment above 10% or insufficient jobs, but tightening these exemptions ignores local labor market nuances. In some states, high-unemployment pockets persist, yet waivers are denied, leaving residents caught between policy and survival. The result is a patchwork system where need doesn’t always dictate aid.

Then there’s the SNAP Employment and Training program, touted as a bridge to work. A USDA review from 2004-2022 highlights its potential, particularly in apprenticeships and customized training. But these programs often reach only those with fewer barriers, and their long-term impact fades without sustained support. For many, the administrative maze of documenting compliance or navigating training while maintaining eligibility is a trap, not a ladder. The USDA’s vision of work as a universal fix glosses over these complexities, offering a one-size-fits-all solution to a multifaceted problem.

A Legacy of Missteps

SNAP’s history reflects a tug-of-war between compassion and control. Born in 1964 to combat hunger and support farmers, the program expanded through the 1970s to standardize aid. The 1980s brought cuts under President Reagan, followed by the 1996 reforms that reshaped welfare. Those changes, while reducing cash assistance caseloads, shifted many onto SNAP, which became a critical safety net. During the Great Recession, the 2009 Recovery Act boosted benefits, helping millions weather economic turmoil. Yet, the pendulum swings back with each political shift, and today’s USDA stance echoes the restrictive ethos of the 1990s.

The current push to limit waivers and enforce work rules isn’t new; it’s a revival of old arguments that work requirements spur self-reliance. But the data tells a different story. When waivers are lifted, SNAP participation among ABAWDs drops by 31-70% in some states, with no corresponding rise in employment. The USDA’s own enforcement efforts, including oversight of state compliance, reveal a system strained by bureaucracy. As of April 2025, 33 states fail to process applications on time, delaying aid to families in need. This isn’t efficiency; it’s a system buckling under its own weight.

A Call for Compassionate Reform

There’s another way. Advocates for food security and economic justice argue for a SNAP that prioritizes people over politics. Voluntary, skills-based training programs, paired with wraparound supports like childcare and transportation, show promise in building lasting employability. Unlike mandatory work-first models, these approaches align with local job markets and individual needs. The USDA could redirect its energy from policing waivers to scaling these programs, ensuring they reach those most in need.

Critics of lenient waivers claim they foster dependency, but this view ignores the structural realities of poverty. Jobs aren’t always available, and training isn’t a quick fix. A truly effective SNAP would expand access to apprenticeships and postsecondary credentials, not penalize those caught in economic crosswinds. It would streamline compliance to reduce administrative burdens, not add hurdles that push people out of the program. Above all, it would recognize that food security is a foundation for opportunity, not a privilege to be earned.

The USDA’s current path risks repeating past mistakes, prioritizing cost-cutting over human dignity. But SNAP can be a beacon of hope, not a bureaucratic gauntlet. By investing in people, not restrictions, we can build a system that lifts up rather than casts out. The choice is clear: reform SNAP to empower, not exclude, those striving for a better future.